Mediating Between Nature & Imagination:

Sudo Hisao

Deidre May (from KJ#52)

Photographer: Ikeguchi Koji

Sudo Hisao's latest sculpture, not yet dry, stands in his ceramic studio: a giant acorn, bursting with life, erotic tip pointing upwards. Around it, a snake is coiled protectively, its gaze unwavering, piercing, inscrutable. Though it is poised to fight if necessary, Sudo doesn't think of the snake as attacking.

"Nature is not aggressive," he says, explaining that while this species' venom can be fatal, the snake is holistically beneficial to the ecosystem. The locals of Amami Oshima, where it is found, both fear and revere it, using its skin pattern as a weaving motif, to wear as a talisman.

Amami Oshima is one of the Ryukyu Islands, a long archipelago extending from southern Japan to northeastern Taiwan, consisting mostly of the exposed tops of submarine volcanic mountains. For the past decade, Sudo’s primary inspiration has been the ecology of this pristine island, which is mostly covered by rich, virgin forest.

"Amami Island is a prism through which I view the world and then reflect it in my work," he says, his eyes sparkling.

Most of Sudo's pieces are larger than life. He creates from a passion for life that accords a visceral energy to each of his sculptures. Their unexpected associations draw us in to marvel intuitively at the endless overlapping of all living creatures. Sometimes dark, at times light, they are always playful. Sudo believes that through inter-relating with the natural world we can rediscover a balance that shifts us away from our errant sense of being the center of the universe.

"I look for nexus points where processes or life forms seem to overlap. They are sometimes difficult to find, but when I locate them, that is where I begin my work."

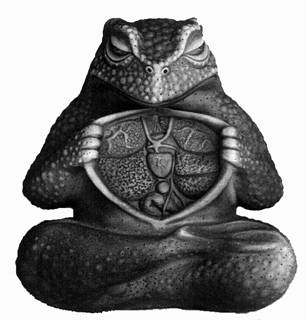

As an artist, he is a mediator between the realm of nature and the imagination. His pieces, like life, are never static; there is always a sense of process or transformation. Some of his work is direct, like the black hare opening its heart, urging us to reciprocate. The ancient, rare and endangered amami-no-kurousagi is endemic to Amami and just one other island. It is designated as a national treasure; one of only three such species that still exist.

Another piece reflecting the ever-shifting faces of nature is based on Odoru Kenmun, a forest sprite in Amami mythology. This creature has the magical ability to shape light on his fingers when fishing, and playfully entices humans to play at sumo with him. Sudo has given Kenmun three faces: on one side a traditional comedic mask called Hyotoko; on another, the beaming Ebisu, one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune, who favours fisherman with big catches. The last is an oni, a fearful demon.

"By watching nature closely, one begins to feel the essence, the life force. I believe in animism, and in the interconnectedness of all living creatures. By looking at the patterns in nature, sometimes I find answers and sometimes questions. I am always thinking about nature, not always understanding but always observing and following the trails that crisscross.

"I make connections with the natural world and then my ceramic works are a way of connecting with other people. I hope that my sculptures are a reminder to relate to life and nature in a way that we have forgotten. My art arises where language ends. Sometimes words have the power to emphasize one meaning to the exclusion of others. I want people to be free to find their own interpretation, make their own connections."

An insect called mai mai kaburi and a snail seem locked in a sensual embrace; looking more closely, one realizes that the snail is being eaten.

"All the world is developing; some aspects are dying while others are renewing. To live and to die are the same. From birth the process of death begins; front and back are the same." From his studio storeroom, Sudo brings out another piece, a peach pit greatly enlarged. One can move around it as if orbiting a planet. Moving closer, its details seem chaotic but as one pulls back, patterns emerge.

"This seeming chaos can be confusing yet is also the basis of a greater stability and peace. Diversity is intrinsic to peace. In the same way, life may seem chaotic on the surface but it is this very interconnected chaos that makes up larger patterns of structure and order."

Since Sudo Hisao's sculptures are imbued with immensely detailed observation, samples from nature are essential. The studio is filled with objects he's collected or been given by friends who work in fields of conservation and ecology. Skulls ranging from sea animals to land mammals hang from the walls; landmarks on the journey of how species have evolved, physically and consciously. Sudo speaks of how malleable and adaptable bone can be, often more flexible than the thoughts it houses.

"I am interested in the origins and evolution of the human race. We started in Africa and that is where both our noblest and basest traits also began."

Sudo traveled to Tanzania last year, to one of the places where the oldest known hominid fossils have been unearthed. "I wanted to stand in the same place as our early ancestors did, feel the sun and the wind, breathe the air, smell the fragrance."

He opens drawers, revealing a small collection of ancient tools. "Where did art begin? From earliest times, hunting and carving tools were decorated. They did not need to be as beautiful as they were, but the desire to create comes from an innate sense of beauty."

For the past 24 years Sudo has been making his ceramic sculptures in a valley near Sonobe, a town north-east of Kyoto. Silence pervades, save for the wind rippling the grass between the rice paddies that rise up in terraces to forested hills. He lives with his wife and teenage son; a daughter studies art in Kyoto. Part of his time is spent farming his rice paddy and vegetable gardens, in a closely-knit community. And when he is not working the earth, he is in his studio working clay.

The story of how his art has evolved reflects the maturation of his relationship with nature. In his early 20's, Sudo started his career as a commercial photographer. He became dissatisfied with the medium, though, because he disliked having to wait for the right shot. He wanted a more active role in the creative process, to be able to choose the end, and more, to touch his work.

Then he met Yoshimura Shunichi, a ceramics master whose area of specialization was the potential of materials. Yoshimura had written books based on his extensive experimentation with varieties of clay and glazes and ranges of firing temperatures. For six years Sudo studied pottery under him, continuing to work as a freelance photographer and also taking shifts in a grocery store. Yoshimura constantly challenged his students to experiment, allowing them free creative rein.

Watching the way his sensei lived and worked, his acute observation and mindfulness, the way he developed theories and then always tested them, Sudo was greatly inspired. In the early stages of his career he made functional ceramics, yet wove mythological elements into their design. Gradually he moved towards making sculptures.

An exhibition in Sonobe in 1984 was a turning point. He used two spaces, one a traditional tatami room filled with utile ceramic ware, the other a modern room showing a series of his early sculptures inspired by nature: a range of frogs in the process of moving through a leap; two snails looking at a real snail shell with the same spiral design as their own.

The following year Sudo held an exhibition in Tokyo, that he called Nuclear Zoo. So that people could grasp the scale of global nuclear production, he made 53,000 miniature warheads; his tally mirrored the actual number of nuclear weapons accounted for in the world at that time. Along with these, he made small-scale animal sculptures; stark, frozen in position, offset against the whiteness of a nuclear winter. Out of this exhibition he created a book of photographs, accompanied by the poems of Kawasaki Hiroshi. One striking line: "They say dogs and horses also dream. I hope we humans are not in their nightmares."

For the past six years, Sudo has been working on his Amami series; he expects that this will culminate in a show two years from now, and is looking for a suitable exhibition space.

How remarkable it is that a visionary artist of Sudo's talent is so little known! His work possesses spirit which surpasses mere mastery of technique and skill. When one lives purposefully, one is always changing, one's heart and mind and spirit. Even he can't predict what his future work will be; it will arise as the inspiration takes him.

"I don't like 'why' and 'because.' Instead I want to play, always to keep playing."

One sculpture is a ball of snakes, grapes and frogs, all massed together. "When you look very closely," he asks, "how do you tell where plants end and animals begin?".

One wonders, looking at Sudo's work, where do we begin and end? Difficult to even say where the body leaves off -- is it at the tip of the finger or in the DNA? His vision extends beyond his work towards a Gaian politik; the flesh of one's body is the flesh of the earth is the flesh of experience.

In another sculpture, three large tomes are piled on top of each other. The top one, a Bible, is slowly being eaten away by spores growing from its covers. One of the first and simplest of species is regenerating.

"Cycles of nature will prevail, even if man becomes extinct and all records and traces of human civilization vanish. Nature will continue to rejuvenate, new species will grow."

Deidre May, originally from South Africa, wrote this profile as an intern at KJ.

Copyright held by the author

2003年1月発行 京都ジャーナル52号 (和訳:西村みどり)

-自然と想像力を仲介する-

須藤久男の工房には、まだ生乾きの最近作が立っている。いのちが炸裂し、肉感的な先端が上を向いて突っ立っている巨大などんぐりだ。その周りには、どんぐりを守るかのように、蛇がとぐろを巻いている。たじろぐことなく、まっすぐに突き刺すような、この蛇の視線は、底知れず不気味だ。必要とあらば戦う構えだが、久男は蛇が攻撃しようとしているとは思わない。「自然は攻撃的ではない。」と彼は言う。彼の説明によれば、この種の蛇の毒は、命を奪うこともあるが、蛇そのものは、全体としての自然体系にとって有益なものだ。奄美大島に見られるものだが、住民はこの蛇を恐れると同時に、敬ってもいる。皮の紋様は、織物の柄に使われていて、お守りとして身に着けたりする。

奄美大島は、琉球諸島の一部をなす長い群島で、日本の南端から台湾の東北の海域に点在している。その大部分は海面上に頭を出している海底火山の頂からなっている。ここ10年間、豊かな原生林におおわれたこの島の原始そのままの生態系が、須藤のインスピレーションの主な源となってきた。

「奄美大島は、ぼくにとって、いわばプリズムのようなもので、ぼくはこの島を通して世界を見、それを作品に反映させている。」目を輝かせて、彼は言う。

須藤の作品の多くは、実物より大きい。その一つ一つに、生命に対する彼の情熱がこめられ、強烈なエネルギーを帯びている。彼の意表をつく発想は、見るものの心に生物の限りない重層性に対する、本能的な畏敬の念を呼び覚ます。時に暗く、時に明るく、しかしいつも遊び心があふれている。人間は、自然との交わりを通して、自分が宇宙の中心だという錯覚から離れて、バランスを取り戻すことができる、と彼は信じている。

「ぼくは、いろいろな生命のいろいろなプロセスやかたちが重なり合っている接点を探している。それは、なかなか見つけにくいけれど、それを探り当てたとき、そこからぼくの仕事が始まる。」

アーティストとして、彼は、自然界と想像の世界の仲介者である。彼の作品は、生命と同様、決して静止していることがない。そこにはいつも過程、あるいは変容という感覚がある。作品のなかには、胸を開いて、わたしたちに迫ってくるクロウサギのような、直接的にメッセージを送ってくるものもある。これは、古くから奄美大島ともうひとつの島にだけ棲息するアマミノクロウサギで、現在絶滅の危機に瀕している、3種のうちのひとつで、国の天然記念物に指定されている。

常に変化してやまない自然の顔を表現しているもうひとつの作品は、奄美の神話に登場する森の精、踊るケンムンである。ケンムンは、魔法の力があって、自分の指を灯にして、あたりを照らして魚をとったり、いっしょに相撲をとって遊ぼうと、人間を誘ったりする。須藤はこのケンムンに3つの顔を与えた。ひとつの面は、ひょっとこと呼ばれる伝統的なこっけいな顔、もうひとつの面は、七福神のひとつで、漁師に大漁を約束するといわれている、笑みをたたえた恵比寿、そして、最後は恐ろしい顔をした鬼である。

「自然をじっくり見ていると、その本質であるいのちの力を感じられるようになる。ぼくはアミニズム、つまり、すべての生き物がお互いにつながっているということを信じている。自然の中にあるパターンを見ていると、答えが見つかることもあるし、問いが見つかることもある。いつも自然について考えている。いつも理解できるというわけではないけれど、いつも観察して、絡み合った小道をたどっている。」「まず、自然界とつながりをつくる、それから、ぼくの焼き物は、他の人たちとつながるひとつの方法になる。ぼくの作品が、忘れ去られている、いのちや自然とのかかわり方を思い出すきっかけになったらうれしい。ぼくの作品は、言葉が終わったところから始まる。言葉というものは、しばしば、ある面を強調する力があるけれど、他の面を切り捨ててしまう。ぼくの作品を、見る人は、それぞれ自由に理解してほしいし、自分なりのかかわりを持ってほしいと思う。」

マイマイカブリという虫と、カタツムリが、奇妙に絡み合っている。よく見ると、カタツムリは食べられようとしている。「この世界ではすべてが、発展しつつある。死につつある面もあるけれど、新たに生まれつつある面もある。生きることと死ぬことは同じことだ。誕生の瞬間から、死のプロセスが始まっている。表と裏も同じことだ。」

工房の奥の倉庫から、須藤はもう1つの作品を持ってきた。これまた大きく拡大された桃の種だ。見る者は、ちょうど惑星の周りを衛星が回るように、この種の周りをまわることができる。近づいてみると、その細部は混沌としているが、下がってみると、あるパターンが見えてくる。『この混沌とみえるものは、ぼく達を混乱させるようだけれど、実はそれこそがより大きな安定と平和の基盤だし、多様性があるからこそ、平和がある。同じように、生命は、表面的には混沌としているように見えるけれども、より大きな構造のパターンや秩序を作っているのは、まさにこの相互につながりあった混沌だと思う。』

須藤久男の作品はどれも、非常に細かい観察から生まれているので、自然界からのモデルがきわめて重要である。工房にはさまざまな標本が所狭しと並んでいて、自分で集めた物のほかに、自然保護やエコロジーに関わる分野で活動している友人達から送られた物も多い。

壁には、海洋生物から陸棲の哺乳類にいたる様々な動物の頭蓋骨が掛かっていて、生物の体と意識が進化してきた跡を辿るようだ。須藤によれば、骨という物は、非常に柔軟で適応性に富んでいて、頭の中に詰まっている考えより頭蓋骨の方がしなやかだということも多い。

『僕は、人類の起源と進化にすごく興味がある。人類が生まれてきたのはアフリカで、人間の最も高貴な面も野卑な面も、アフリカから始まっている。』須藤は去年、最古の人類の化石が発掘された場所のうちのひとつであるタンザニアを訪れている。『僕達の祖先が立ったのとおなじ場所に立って、おなじ太陽と風に触れ、同じ空気を吸って、同じにおいをかぎたいと思った。』そう言って、引出しを開けると、古代の道具のちょっとしたコレクションを見せてくれた。

『芸術はどこではじまったんだろう?ごく初期の時代から、狩の道具や、削る道具などには装飾がほどこされている。そんなに飾る必要はなかったのに。創造したいという欲求は、人間に本来備わっている美の感覚から来ていることがわかる。』

須藤はこの24年間、京都の北東にある園部町郊外の盆地で作陶を続けている。静けさに包まれて、聞こえてくるのは周囲を丘に囲まれた棚田のあぜの草を吹き抜ける風の音だけだ。

彼は、ここに妻と10代の長男と一緒に暮らしている。長女は京都で美術を学んでいる。この村の一員として、田んぼや菜園で作物を育てるのも、彼の生活の一部だ。外で土を相手に働いているか、さもなければ工房で粘土を相手にしている。

彼の芸術がどのように進化してきたかという物語は、そのまま彼の自然とのかかわりの成熟のプロセスを反映している。20代の始め頃、須藤は商業カメラマンとして仕事を始めた。しかし、カメラという媒体には、不満を感じるようになっていった。シャッターチャンスを待たなくてならないというのが嫌だった。創造のプロセスにもっと積極的に関わりたい、どういう作品を目指すのかを自分で選びたい、さらに、自分の作品に触りたい、と思ったのだ。

その頃、彼は、陶芸の大家である芳村俊一に出会った。芳村は、素材の可能性の研究を専門とし、さまざまな粘土や釉,焼成温度での広範な実験に基づいた著作もある。須藤は、フリーのカメラマンとして働きつづけながら、そしてさらに、食料品店でも働きながら、芳村の下で、6年間、陶芸を学んだ。芳村は、彼の弟子達に、いつも新しい試みに挑戦するように促し、自由に創作することを勧めた。先生の生き方、仕事の仕方、その鋭い観察とひたむきな姿勢、新しい理論を開発し、常に実験を通して確認するやり方は、須藤に大きな影響を与えた。

陶芸作家として仕事をはじめた初期には、実用的な陶器を作っていたが、そのデザインの中にも神話的な要素を織り込んでいた。やがて次第に彫塑の方へ向かうようになった。1984年に園部で開かれた個展が、その転機となった。会場は二つの部屋に分かれていて、一方の和室には、実用的な作品が展示された。もう一方の洋室には、自然を題材にした初期の彫塑作品が並べられた。かえるが跳躍する過程をとらえた連作や、二つのカタツムリが、自分達の殻と同じ渦巻き模様のある本物のカタツムリの殻を見つめている作品などだ。

その翌年、須藤は東京で、原爆動物園と題した個展を開いた。彼は、この展覧会で、地球上で行われている核兵器製造の規模がどれほどかを伝えるために、53000個のミニチュアの核弾頭をこしらえた。これはその当時世界に実際存在していた核兵器の数だった。また、これと平行して、真っ白な核の冬の世界に、こわばって、凍りついている小さな動物たちの像を作った。さらに、この展示作品をもとに、その次の年に写真集を作った。そこには、川崎洋氏の詩が添えられているが、なかでも次の詩は衝撃的だ。

『犬や馬も夢を見るらしい。動物たちの恐ろしい夢のなかに人間がいませんように。』

最近6年間、須藤は奄美をテーマにした連作と取り組んでいる。2年後には、これらの作品をまとめて、個展を開く予定で、適切な会場を探している。

須藤ほどの豊かな才能に恵まれた作陶家がこれほど知られていないというのは驚くべきことだ。彼の作品には、卓越した技巧とか技術を超えた精神が宿っている。何かを目指して生きている人間は、その心も意識も精神も常に変化しつづける。須藤は、今後自分の作品がどうなって行くのか、自分でも予想できないという。それは、インスピレーションに誘われるままに、生まれてくるだろう。『なぜとか、なぜならば、とか言うのは、好きじゃない。そうじゃなくて、僕は遊びたい、いつもあそびつづけていたい。』

何匹もの蛇や、ぶどうやかえるが絡まりあって球になっている作品がある。『よく見てください。どこで植物が終わって、どこから動物が始まっているか、わかりますか?』と彼は尋ねる。須藤の作品を見ていると、自分達もどこから始まりどこで終わっているのだろうと考えてしまう。身体というのもどこまでなのか、これも答えにくい。指の先までか、それともDNAまで続いているのか?須藤の視野は、作品を超えて、ガイア・ポリティクにまで広がる。身体の肉は地球の肉であり、それが体験の肉である。

三冊の分厚い書物が積み上げられている作品では、一番上にのっている聖書が、その表紙から生えている菌類によって、徐々に蝕まれている。最も原始的で単純な種である菌類が再生している。

『結局は、自然のサイクルが続く。たとえ、人類が絶滅しても、人間の文明のあらゆる記録や痕跡が消滅しても、自然はまた若返り、新しい種が生まれることだろう。』